French Army C-36: The Allied period

( )

(

)

( )

)

C-36 Home Page

6.1 The historical context

In November 1942, the Allies landed in French North Africa (Operation Torch). The Vichy troops resisted but were quickly defeated.

After the Anfa Convention in January 1943 (Morocco), under American pressure, De Gaulle's FFL [1] and Giraud's regular army of North Africa merged. At the beginning of 1944, five DIs and three DBs were formed [2]. Three components emerged:

- Army A (then called CEF [3]), led by General Juin, which fought first in Tunisia (From November 1942 to May 1943), then in Italy (From November 1943 to July 1944).

- The First French Army [4], (at first called Army B), led by General De Lattre de Tassigny, which landed in the South of France in August 1944 (Operation Dragoon).

- The 2nd Armored Division (2eDB), led by General Leclerc, which landed in Normandy in August 1944.

In September and October 1943, General Giraud (against the advice of De Gaulle) liberated Corsica.

Footnotes:

- [1] FFL: “Forces Françaises Libres”: Free French Forces.

- [2] DI: “Division d’Infanterie”: Infantry Division, DB: “Division blindée”: Armored Division.

- [3] CEF: “Corps Expéditionnaire Français”: the French Expeditionary Corps.

- [4] The French First Army was made up of seasoned troops (those of General Juin) and those who were in training in North Africa.

6.2 French encryption – From frequent changes in procedures to the withdrawal of the C-36

From late 1942 to August 1944, a part of the French Army trained. At the beginning, the encryption method already available during the Vichy period was used but gradually the American M-209, introduced into the French Army from May 1943, establishes itself as the principal means of encryption for small units and replaces the C-36.

At the same time, another part of the French Army was fighting in Tunisia. The staff exclusively used the B-211 and C-36 (SHD-10P237) [1].

Regarding the Italian campaign led by General Juin, I could not find any information at SHD that indicated whether or not the C-36 was used. Nevertheless, it is likely that the French contingent was equipped (among others) with the C-36.

In May 1943, a document (SHD-11P189 1944) lists the encryption methods used by the 1st DB: the B-211, C-36, code 72, ATM code, and the process without dictionary type 1943 (modification of process SD 1923 with diagonals).

In addition, the following is specified:

- B-211: normal means of encryption for armies and army corps.

- C-36: normal means of encryption up to regimental level.

From the end of 1942 to July 1944, the procedures for using the C-36 became increasingly complex to compensate for its lack of security. Finally, at the end of July 1944, the C-36 was withdrawn from active service. Here is the document announcing this withdrawal (SHD-11P189 1944):

ARMEE "B" – Bureau du Chiffre - No 172/2 CH-TS - Reference:

Standing Instruction for Transmissions, No 10, of July 25, 1944.

(Red stamp "VERY SECRET")

Subject: Return of encryption procedures - Memorandum -

The referenced standing instruction specifies which encryption

methods are currently authorized for use in operations under

the provisions adopted by the U.S. 7th Army.

1e- Converter M.209 (used according to the instructions in force

in the United States Army - See: Instructions for the use of

Converter M-209A, Part No 7-1 of 7/25/44 of the weekly order of

the Command of Transmissions.)

2e- SD 43 process ...

Thus will be donated:

- The EMPIR codes and their superencipherment system.

- The C36 machines as well as all the instructions and notices

concerning their use and the last telegram received concerning

their keying.

- All instructions and notes from the Bureau du Chiffre or the

army concerning the use of Converter M-209 according to the

modalities that were adopted in North Africa, including the

complete copies of the collections of 60 "SIGRBA" tables and

the last telegram received regarding periodic changes to these

instructions.

- The ATM 1943 codes and their superencipherment system.

- The Codes 72 and their superencipherment system.

Regarding the index of conventional abbreviations No 733 CH/CAB,

it will not be returned, the first part of these provisions

remaining in force ... The transfers prescribed above do not

apply to the army corps with regard to their own endowment.

The units which, following these transfers, would find themselves

deprived of cipher procedures, will use AFCODE [3] for their secret

messages combined with the cartographic coordinate code and the

authentication table …

After this date (end of July 1944), the C-36 seemed to disappear from

theaters of operations. The set of encrypted documents that revealed

method of encryption no longer indicated the use of the C-36. Thus,

the indicators written in pencil on the messages were now those of the

M-209 or the B-211. The most common indicators were composed of six

letters framed by two groups of two identical letters. This signature

indicated the use of the M-209. The indicators of the B-211 were also

easily recognizable. When I obtained messages in the form of printed

tapes, it was only the characters of the B-211 or M-209 that showed

through.

The last unencrypted message intended for encryption in C-36 that I found in the archives dated from July 12, 1944. It corresponds to a message exchanged between Oran and Constantine, that is, inside North Africa, which is in the hands of the Allies (SHD-1460B10 1944).

Note: TICOM documents make it possible to follow the evolution of procedures, in particular indicator methods, but from the point of view of the enemy (cf. 6.4).

Footnotes:

- [1] I was able to deduce this from the pencil markings that contained the indicators. Frequently, the means of encryption appeared (C-36 or B-211). When the same indicator system was used, I assumed that the same means of encryption was used.

- [2] The code “Empir” is also spelled “Empire".

- [3] AFCODE is an American encryption system for small units. It is a disordered code of two letters (bigrams) which therefore has two parts (one ENCODE part and another DECODE part).

6.3 Use of the machine

6.3.1 Endowment

The following document indicates the endowment of a territorial division with material and documents for encryption in July 1943 (SHD-11P189 1944). The main encryption method is C-36, but the division also has ATM and 72 codes. The CERES envelope contains the current key for C-36 (cf. 6.3.4). Other documents from the same period mention an additional document "the list of C-36 holders" and the conveyor belt.

Inventory of the documents of the Bureau du Chiffre given to the

territorial division of Oran - July 14, 1943

- Secret instruction 35/SCH N° 63 (1) [1]

- Memento guide 34/SCH N° .... (1)

- SD 43 N° 1186 (5)

- Code 72 N° 32-33-34-35-36 (5)

- Key tables N° 3-4-5-6-7 (5)

- ATM code N° 124 (1)

- LATEM [2] 90 EM/CH-TS N° 124 (1)

- SIEVE 105 EM/CH-TS N° 124 (1)

- Instructions for using the C36 13311/EMA cipher machine (2)

- Notice relating to encryption by C.36 N° 160 EM/CH-TS.

No. 143-142 (2)

- Encryption machines C.36 N° 6-538 6-552 (2)

- Note S-2120 CH/FT use of abbreviations for C.36 (1)

- Commissioning instruction C.36 N° S 15470 EM/EMA (1)

- N° 252/EM-CH- Encryption by C.36 N° 251-252 (2)

- N° 427/EM-CH-TS Encryption by C.36 N° 090-091 (2)

- CERES 161. EM/CH-TS envelope N° 142-143 (2)

Footnotes:

- [1] The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of copies of the item.

- [2] The LATEM and TAMIS envelopes contain the superencipherment keys for the ATM code.

|

|

6.3.2 Preparing messages – Drafting

The archives of the first DB (SHD-11P187 1944) are full of telegrams with the machine-printed tape as well as the text of the unmarked message. Here are some of the abbreviations observed:

GAL Général (General) CHIF Chiffre (Bureau du Chiffre)

DS Dans (in) REF Référence (reference)

LT Lieutenant (Lieutenant) OFF Officier (officer)

VS Vous (you) DIV Division (Division)

COL Colonel (Colonel) MESS Message (Message)

PR Pour (for) ASPT Aspirant (Aspirant)

CDT Commandant (Commander) RGT, REGT Régiment (Regiment)

TELEG Télégramme (telegram)

MESAGE instead of MESSAGE (message)

HEUR for “heure” (time)

COMDMT for “commandement” (command)

S, SP, TS, STP, STOP for the word STOP (sentence separator)

NUM, NR, NO instead of “numéro” (number)

In addition, a number of messages, almost one in two, began with

NUMKW ... KSURKW – the two strings separated by two, three, or

four characters. We recall that "K" means "space" and "W" begins

a string that must be interpreted as a number. This string

therefore represents the message number. The chapter that

describes the methods of the German cryptanalysts demonstrates

that the use of stereotyped beginnings is a serious breach of

security (cf. 5.5). In fact, most of

the German decryptments of the C-36 were based on the use of

stereotypical beginnings.

Here are other frequently used beginnings:

NOKW, NUMK, or NRKW to mean "NUMBER ###"

REFK, REFERK, or REFERENCEK for REFERENCE to a message.

PRK (for) or DEK (from) followed by the indication of a person (CDT … ) or a unit.

Conversely, the end of the message was frequently indicated by the word "FIN" (end).

Since many messages were poorly transmitted or poorly encrypted, many messages requested that the message be repeated and ended with the word “INDECHIFFRABLE” (indecipherable) followed by 0 or more spaces.

Note: In this period, the printed tapes of the messages glued to the back of the slips for C-36 and M-209 messages were mixed. I could easily discern the machine producing the tape. Indeed, the spaces are not coded in the same way: if the message included "K," it was encrypted in the M-209 and if it included "Z," it was encrypted in the C-36. In addition, several letters (D, P, R, M, A … ) in the two machines had different typographies. The rare B-211 messages were indicated by the presence of special characters (numbers, +, -,% … ). Figure 1 [1] shows an example of a decryption tape from a C-36. Figure 2 shows a decryption tape from an M-209.

Footnote:

[1] In Figure 1, we note the presence of the letter Z and in Figure

2 the presence of the letter K. These letters, Z and K, correspond

to the encryption of the space in the M-209 and the C-36, respectively.

|

|

6.3.3 Preparation of messages –

Packaging (December 1942 to December 1943)

In the archives, I found several circulars that specified the location of the two key groups (SHD-11P189 1944). Figure 3 corresponds to the first telegram. It uses a form that is of French origin.

PC. October 10, 1943 - Undrafted decryptment of an encrypted

telegram - (SECRET stamp) Gustave to Danaide - Departure from

Algiers on 10/9/43, Received by Bureau du Chiffre on 10/10/43,

Telegram number: 844/CH/CABINET - Plain text - For 2e Bureau,

Bureau du Chiffre - Request for acknowledgment of receipt [1]-

From October 15, midnight - observe the following rules for

C36 encryption:

- First: Place immediately before the 1st key group 3 null groups.

- Second: Formal prohibition to use a pronounceable word for key

formation or to use the same key for different telegrams; offenders

will be severely sanctioned –

Here is the second telegram:

TELEGRAM TO BE ENCRYPTED - Danaide to Base-Destructeur-digitale-

Deesse-Artillerie divisionaire - Text - N ° 134/2-CH. From November

20 at midnight, the packaging of ciphered telegrams by C36 machines

will be as follows: Firstly, group date, number of groups. Secondly,

a field of three null groups. Thirdly, first key group. Fourthly,

second key group. Fifthly, cipher text STOP Please acknowledge

receipt ... Signed Joubert des Ouches

PC. 11/13/43 - General TOUZET du VIGIER, Commander of the 1st

Armored Division [2]

By Order: The Chief of Staff

It can be seen that the two key groups are no longer directly at the beginning

(or at the end) but instead preceded by three null groups. We also observe the

statement of well-known security rules:

- Do not use a pronounceable word for the message key.

- Do not reuse the message key.

Another document (undated) specifies that the header of the message (date group, number of groups) as well as the division of the cryptogram into groups of five letters corresponds to a signature of the messages: this made it possible to deduce that they were encrypted by means of the C-36 [3]. Here is the example provided (SHD-11P189 1944):

22.015 DHAPR HRVTM ... (22nd day of the month, 15 groups, cryptogram)

In the archives, I also found a memo that limited a telegram to 500 letters

(SHD-11P189 1944):

20 Dec 1942 – Memorandum – telegrams limited to 80 groups, in

exceptional cases to 100 groups.

I do not think that this limitation is linked to security but rather to

smoothing traffic flows. Indeed, encrypting a message is a long procedure

(about 1/4 hour for 200 letters). Nonetheless, a large number of erroneous

messages are transmitted. The longer the messages, the greater the number

of errors and therefore the greater the number of repetitions. In the C-36

messages that I saw, I rarely observed messages larger than 300 letters

(60 groups). To comply with this rule (maximum 100 groups), long messages

were sent in several parts. I observed these types of messages frequently.

Each part was encrypted with a different message key and thus had a

specific indicator.

Note: All the information that I give on the headers of the messages as well as on the indicators is taken from data derived from the slips containing the plain text of the messages. I was not given access to any encrypted messages that could have confirmed my assertions.

Footnotes:

- [1] In the French text, the military term "Accution" was used to request an acknowledgment of receipt.

- [2] We learn incidentally that the code name "DANAIDE" corresponds to the first DB.

- [3] Conversely, a message encrypted with the code 72 began with the number of groups followed by the message in the form of groups of four letters, for example: "0015 PLYA RBOM ..."

6.3.4 Key distribution (November 1942 to April 1944)

During the Free France period (1943, 1944), new procedures emerged.

At the very beginning of the engagement of the French alongside the Allies, it was the means of encryption and the keys in force that were used. Thus Tables A, B, and C N° 232/EM.CA/TS of C-36, which had been put into service on August 21, 1942, were used until mid-January 1943. They were only incinerated on August 21, 1944 (SHD-11P189 1944).

From January 1944, the keys related to the encryption processes, in particular those of the C-36, were mainly distributed inside a sealed envelope bearing a keyword. The slip associated with the delivery of the envelope specified the date on which it was put into service, but this could be anticipated if its holder received a telegram from the Bureau du Chiffre containing the key word. When the new key was put into service, the old one was incinerated. Here are the envelopes for the C-36 that I found [1]:

- The BETA envelope sent on December 7, 1942 (I do not know when it was put into service).

- The JUPIN envelope sent on December 25, 1942 (I do not know when it was put into service). It was cremated on April 15, 1943 when the CERES envelope was put into service.

- The CERES envelope, put into service from April 15, 1943, was still in service at the beginning of November 1943.

- The PERMA envelope sent on February 16, 1944 was put into service from April 1, 1944 at midnight. The associated key remained in effect for the entire month of April.

- It is possible that the BETA envelope (and possibly also the JUPIN envelope) was never commissioned. In fact, a slip indicates the issuance and entry of keys into service from January 21, 1943, replacing keys from the Vichy period. These keys are named under their classic name (Tables A and B) instead of using the name of an envelope.

- A document dated January 30, 1944 records the incineration of a CERES envelope. We can deduce that the key associated with this envelope expired at the end of January 1944 at the latest.

- The CERES envelope was distributed with another envelope with the same number but bearing the name "Machine C-36." I think its contents specified the procedure and the use of the indicator system (which conceals the message key).

A few months later (April 14, 1944), another document requests their incineration: "Order to incinerate secret notice n ° 986 of 11/11/1943 relating to encryption by C36 machine." Figure 4 corresponds to the delivery note for the key in December 1943.

Regarding this last envelope (PERMA), I found its distribution list in the archives, which specifies the number of envelopes each recipient receives and the number of each copy. In total, there were 187 envelopes, which were all intended for members of the C-36 network of French units in North Africa (a priori one envelope per machine). The main recipients were Army A, Army B, and 19 ° CA. Here is, for example, the sixth recipient, the 19th Army Corps and all the units of which it is composed:

6° / - Mr. General Commanding the 19 ° CA - 2e Bureau – Bureau

du Chiffre – ALGIERS-: 30 copies (n ° 70 to 99) For allocation

of all the territorial divisions, subdivisions, and bases in

the possession of Machine C-36 (AIR included).

Footnote:

[1] The C-36 was not the only system that used envelopes. Thus, the

superenciphered keys of the ATM code were transmitted by the LATEM/TAMIS

envelopes and then SATIM. The superenciphered keys of the Empir code were

transmitted by the KASOR envelope and then LIPAL. Even the M-209 used the

ARMIC envelope for a while.

6.3.5 Key distribution (May, June, July 1944)

From May 1944, the keys were transmitted by radio. Following is a reproduction of the documents. Because they were transmitted over the air, I found several copies: especially in each unit receiving the key. The following keys were received by the 1st Armored Division belonging to the B Army, which will land in the south of France (SHD-11P189 1944).

6.3.5.1 The key to May 1944

04/24/44 - (VERY SECRET stamp)

1st ARMORED DIVISION – General Staff – 2e Bureau –

Bureau du Chiffre No. 66/2 CH-TS. PC April 24, 1944

Active positioning of internal secret elements for C.36 machine,

valid from May 1, 1944:

LE ZOUAVE DU PONT DE L'ALMA A DIT -

LA VIE EST UNE LUTTE CONSTANTE -

ON A SOUVENT BESOIN D'UN PLUS PETIT QUE SOI -

RIEN NE SERT DE COURIR -

IL FAUT PARTIR A POINT -

Verification of the 26 letters (take L as the “calage” letter)

WEIXY JHSLL ETAZE HPZXJ CULWI S

The General of Division, TOUZET DU VIGIER, Commander of the 1st

Armored Division. PC Lieutenant Colonel LEHR, Chief of Staff.

Recipients:

Tank Brigade, Support Brigade, Divisional Artillery, Divisional

Infantry, Base, 3rd R.C.A, Souche.

6.3.5.2 The June 1944 key

05/24/44.- (VERY SECRET stamp)

1st ARMORED DIVISION - STATE-MAJOR – 2e Bureau –

Bureau du Chiffre No.99/E CH-TS. PC May 24, 1944

Active positioning of internal secret elements for C.36 machine,

valid from June 1, 1944:

LA ZONE DANGEREUX EST A FRANCHIR -

UNE HALTE EST NECESSAIRE -

POUR ETABLIR LA JONCTION -

LE MAUVAIS TEMPS RETARDERA NOTRE ??UVEMENT -

[mouvement ?]

ATTENDRE ORDRE D'URGENCE POUR PASSAGE -

Verification of the 26 letters (take L as “calage” letter)

JEYWF EESSJ HQGLL TFJYX CVAHP SQFMF.

The General of Division, TOUZET DU VIGIER, Commander of the

1e Armored Division. PC Lieutenant Colonel LEHR, Chief of Staff.

Recipients [1]:

Tank Brigade, Support Brigade, 1/2 Zouaves Brigade, Base,

3rd R.C.A, Souche.

Footnote: [1] The last two key tables are for the same recipients.

6.3.5.3 The July 1944 key

1st ARMORED DIVISION - STATE-MAJOR – 2e Bureau –

Bureau du Chiffre No. 97 CH-TS. PC June 23, 1944.

(VERY SECRET stamp)

Active positioning of internal secret elements for C.36

machine, valid from July 1, 1944:

NOS APPAREILS A LONG RAYON D'ACTION

ATTAQUE EN FORCE LES AERODROMES ENNEMIS

DE NOMBREUX INCENDIES

SONT SIGNALES AINSI QUE DES EXPLOSIONS

AUCUN APPAREIL EST MANQUANT

Verification of the 26 letters (take N as “calage” letter)

YGKYG OVUGS OVFNX VHBJL GWNSK D

This table cancels and replaces the 79/2 CH-TS, which will be

cremated on July 1 at 24 Hours. Incineration report to be

provided upon execution.

The General of Division, TOUZET DU VIGIER, Commander of the

1e Armored Division. PC Lieutenant Colonel LEHR, Chief of Staff.

6.3.5.4 System operation

From May to July 1944, the keys are transmitted by radio message and are valid for one month. They are encrypted with the old key. The key does not appear directly; it must be deduced from key phrases ("LE ZOUAVE DU PONT DE L'ALMA A DIT"). This method is obviously extremely insecure: In fact, if the enemy succeeds in finding the old key, they know the next one. Indeed, this was the case. In the interview with Otto Buggisch (TICOM I-58 1945), I was surprised to again discover (from the German side) this enigmatic sentence: "LE ZOUAVE DU PONT DE L'ALMA A DIT." This sentence provides indisputable proof that the Germans read French C-36 messages. The dispersion of the units and the lack of means to edit and distribute the keys was undoubtedly the origin of the transmission of the keys by radio.

After several attempts, I was able to reconstruct the coding method of the internal key: WARNING! The astute reader can immediately stop reading and attempt to find this method themselves.

I found the method by wondering about a spelling mistake. In the first sentence of the second message, it reads "LA ZONE DANGEREUX ..." But in French, it should have read "LA ZONE DANGEREUSE … " The presence of the "X" seemed to me to relate to the letter X existing on the first wheel of the C-36 (the one which has 25 sectors). Here is a brief summary of this method: Each sentence indicates the position of the active pins of a key wheel. Take as an example the last line of the last key: "AUCUN APPAREIL EST MANQUANT." List the letters appearing: ACEILMNPQRSTU. The key (pins active) for Wheel 17 is therefore A_C_E___I__LMN_PQ. The letters R, S, T, U have no meaning for Wheel 17.

In the document shown in Figure 5 [1] (SHD-11P189 1944), I had confirmation that the 26 letter verification corresponded to the encryption of the letter "A" repeated 26 times taken as the message key AAAAA.

Regarding the "calage" letter, it does not correspond directly to the slide; it is the letter on the indicator disc that is opposite the number 1 in red on the disc number of the typewheel. The following formula links it to the slide:

Slide = (Calage + 9) modulo 26

For example, if the “calage” letter is the letter "L," the slide will be equal

to 20 (11 + 9). We start the alphabet at zero: A = 0, B = 1, ..., Z = 25.

I discovered the confirmation of this formula in a book dealing with decryption (Muller 1983). Thanks to my simulator, I managed to reproduce the 26 letter check using the "A" lug configuration of Table 2, the one using two overlaps. This fact, in addition to the decryption of the cryptogram of June 1941, confirms with little doubt that only Configuration A of the lugs (Table n° 2) was used during the Second World War.

Footnote:

[1] Figure 5 uses an original U.S. form (M-210). Most typed messages used

French forms, while those written in pencil often used the M-210 form.

6.3.6 Indicator method (December 1942 to December 1943)

In the archives of the SHD (10P237 1943, 10P238 1943, 11P187 1944), I came across a catalog of messages with the raw plain text tapes from cipher machines glued to the back of each message. In addition, the cipher clerk had written three groups of letters in pencil on many of these messages, with the first being almost systematically above the following two. I easily deduced that the first group corresponded to the message key and that the two following groups constituted the two indicator groups, with each encrypted with a different substitution alphabet. Indeed, the fifth letter of the first group never included letters from R to Z and the fourth never included letters from T to Z, and so on. As I had several dozen messages, I was able to reconstruct the two alphabets completely for a given period.

In addition, unlike the method used in May 1940, all the possible keys could be used because a key letter no longer corresponded to two or three letters of a substitution alphabet, but only to one. This method also makes it possible to differentiate a B-211 key from a C-36 key. I also found that now almost systematically (but I have at least one conflicting example) the second indicator group was reversed. Hence, for the 06/22 message, the second group is JNTBF instead of FBTNJ (X = F, D = B, E = T, C = N, A = J).

In the archive, C-36 messages were mixed with messages encrypted in the B-211 and M-209 (from May 1943). It was easy to discern the cipher machine used. Indeed, it was often indicated in pencil on the slips containing the messages, along with (still in pencil) the indicator. Figure 6 [1] presents an example. Those using the M-209 were easily recognizable because the first two letters of the first group were equal to the last two letters of the second group (for example JJMSG TREJJ). Those using the B-211 used the same method as during the Vichy period and only used the letters A through K (with J omitted).

The following tables (6, 7, 8) correspond to the alphabets that I have reconstructed from the slips. The alphabets in Table 6 were used from June to November 1943 and correspond to the period of the CERES envelope. Figure 7 provides an example of a message, key, and indicator belonging to this period. Presumably this envelope also contained these substitution tables. Table 7 contains the (incomplete) alphabets that I reconstructed from messages from December 1, 1942 to January 19, 1943. They probably corresponded to Table B, which was in service from August 21, 1942 to January 21, 1943 (cf. 5.3.2). I have reconstructed the alphabets given in Table 8 from messages dating from January 21 to 31, 1943. They correspond to Table B, which was put into service on January 21 (cf. 6.3.4).

The use of the alphabets from Table 7 shows that the indicator method based on substitution alphabets previously described actually dates from the Vichy period.

Note: Arithmetic operations were written in pencil next to the indicators. Here is a reconstructed example: (940 - 650) ÷ 5 = 58 (cf. Fig 6). I deduced that this was the calculation of the number of groups: the final position of the C-36 counter minus the initial value divided by the size of a group (five characters).

Footnote:

[1] The message in Fig 6 is rare because it was transmitted using the B-211

and C-36. For each method, the method, key, and indicator are shown in pencil.

Table 6: Substitution alphabets from June to November 1943

Date Key Indicator

06/22/43 XDECA HISOF JNTBF

06/30/43 COIHJ OGEJU SPYAN

07/08/43 YROLB XVGPD GUAHR

08/11/43 NIKGO ZELRG AEOYV

10/18/43 POIQJ TGENU SZIAK

11/12/43 GXIPK RHETL OKYFE

11/13/43 RPLJN VTPUZ VSUKH

11/15/43 ZPJLC BVUPO HUSNC

A key letter ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVXYZ (W omitted)

1st alphabet FDOISARJEULPKZGTNVCQMYHXB

2nd alphabet JGNBTMEPYSOUIVAKZHLXDQFRC

Table 7: Substitution alphabets for the period December 1, 1942 to January 19, 1943

Example of an indicator and associated key:

ZKCBV QMIEL - Key: ONKEI

A key letter ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVXYZ (W omitted)

1st alphabet MEXGBSLFVHCPQKZDOUAJYR??N

2nd alphabet GNFXMAKRQUIBTELJYCPVHO??D

Table 8: Substitution alphabets for the period January 25 to February 4, 1943

Example of an indicator and associated key:

LTXYZ EZGMH - Key: HBAFP

Note: the second group is not reversed: EZGMH encodes the

key HBAFP.

A key letter ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVXYZ (W omitted)

1st alphabet XTUOHYPLCQEMDSRZIJAKBG???

2nd alphabet GZSIYMDEBTRVKXPHNUOACQ???

|

|

6.3.7 Digital indicator method – From January 1944

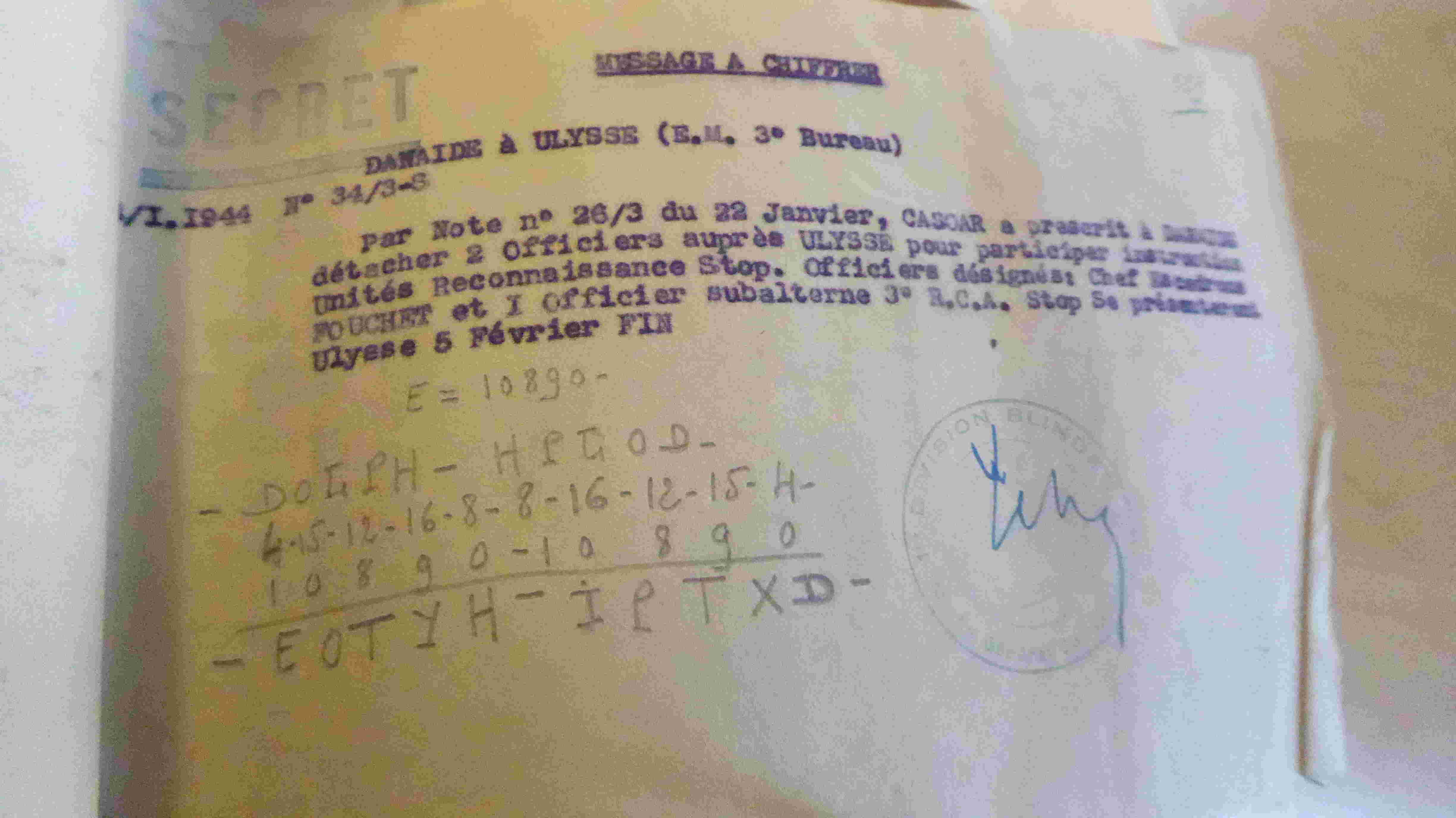

In the period January 1 to February 27, 1944, I observed several annotations written in pencil on eight outgoing message slips (SHD-11P187 1944). Table 9 presents two examples and Figure 8 shows one.

Obviously, these annotations show a change in the indicator method. The use of substitution alphabets has been abandoned in favor of a numerical method. Although I have evidence of this method being used only from January to February 1944, it is likely that this is the method that remained in effect until the withdrawal of the C-36, that is, in July 1944. In the period from January 1 to February 27, the CERES envelope was no longer used a priori and therefore the new indicator method was used with its successor key. This new method eliminated the need to publish new envelopes to change the way the message key was hidden.

Almost every time (but not always), the encryption code was associated with a letter. Here are the codes from seven messages (the same code can be used several times) and the associated letter is called "lettre chiffrante" [1]:

C = 02972, E = 10890, F = 05945, S = 21781

The codes 24754 and 08918 were not associated with a letter.

It seems obvious that the group of the first row (UAPIE in the second example of Table 9) is the message key (repeated backward) and the two resulting groups (UFYMJ ENYEZ) are the two key groups of the indicator, and they are generated by adding the numerical representation of the letters of the key (A = 1, B = 2, C = 3, ..., Z = 26) to each digit composing the numerical code corresponding to the "chiffrante" letter.

The codes have a structure: VWXYZ, with W = Z, V + X = Y + Z = 9.

Why this structure? I think this structure plays a code checking role. This structure only makes sense if the code is transmitted and is part of the message. My opinion is that this group appeared in alphabetical form. The number/letter translation specific to the C-36 should probably be used. Since I could not find any cryptograms from this time, I do not have any examples of using this method.

The aforementioned hypothesis explains a great deal, but not the association of a number group and a letter, called a "chiffrante" letter.

For this period (early 1944), I also found annotations for three messages intended for encryption by the M-209. I deduced that at that time the French Army used the same method to encrypt the message key as that used for the C-36 (SHD-11P187 1944); Table 10 gives an example. This complex method was abandoned in favor of the M-209 and the number management utilized the American method under pressure from the Americans (cf. 6.2).

Here are the codes for these three messages: T = 07937, K = 16846, V = 05955.

We can deduce several things:

- Here also the code masking the "chiffrante" letter respects several rules: W = Z, V + X = 9, but Y + Z = 10 instead of 9, which makes it possible to distinguish M-209 code from C-36 code.

- The first two digits of the codes (07, 16, 05) make it possible to deduce the "chiffrante" letter if we consider the following sequence: Z = 01, Y = 02, X = 03, and so on.

- The "chiffrante" letter corresponds to a letter that is encrypted 12 times and which allows a random message key to be generated. This letter is doubled in the indicator and also indicates that the message is encrypted via the M-209.

The following message from January 1944 plunged me into a pit of perplexity (SHD-11P189):

CEF - 1st Armored Division - General Staff – 2e Bureau -

PC, 11/1/44 ...

Dispatch slip. SIGRBA system in service for setting the

CONVERTER machine key - Copies: 1. Table giving the numerical

groups representing the “chiffrante” letter and key of the

numbers - Copies: 1 …

Hence, a table should exist giving each “chiffrante” letter and its numerical

correspondence. This message is obviously addressed to holders of M-209s

but if the same strategy applies for the C-36, I no longer understand why the

digital code is associated with a letter. The numerical code is

self-sufficient unless the “chiffrante” letter means the “calage” letter.

In short, I formulate the following hypothesis for the operation of this new indicator method. The cipher clerk sets their machine with the current key. He decrypts the group associated with the “chiffrante” letter using the digit matching their C-36. Then, he obtains the sequence of digits (for example, 21781), which allows him to decrypt the message key. The correspondence table between the “chiffrante” letter and the numerical code allows him to validate the code. Moreover, the “chiffrante” letter provided him with the “calage” letter for this message (which is different to the “calage” letter used to decrypt the group associated with the “chiffrante” letter).

The packaging of the messages has obviously changed to include the group concealing the “chiffrante” letter. A message on February 20, 1944 from the Bureau du Chiffre of the 1st Armored Division (SHD-11P189 1944) describes the new packaging of telegrams encrypted by the C-36:

Danaide to Destructeur-digitale-deesse-A.B. Based. TEXT -

N° 27/2-CH-S. Packaging telegrams encrypted by C.36 modified

from February 20, 1944 1 Hour.

1° Group date and number of groups.

2° Group camouflaging “chiffrante” letter.

3° Encrypted text.

4° first key group.

5° second key group.

Other instructions, notice 986 CH/CAB of 11 November 1943

remain applicable.

PC. on February 14, 1944, The Cipher Officer.

Footnote:

[1] The expression "lettre chiffrante" can be translated as the letter

used to encrypt. For the rest of the paper, we will use the expression

"chiffrante letter."

Table 9: Indicator method from January 1944 (digital)

On a message from January 1, 1944

21781

H L A Q F - F Q A L H

8 12 1 7 6 - 6 7 1 12 8

2 1 7 8 1 - 2 1 7 8 1

---------------------------------

J M H Y G H R H T I

On a message from January 18, 1944

F = 05945

U A P I E - E I P A U

21 1 16 9 5 - 5 9 16 1 21

0 5 9 4 5 - 0 5 9 4 5

---------------------------------

U F Y M J E N Y E Z

Table 10: Digital indicator method for the M-209 (1944)

K = 16846

K K E U H N L P K K

11-11- 5-21- 8-14-12-16- 11-11-11-11- 5-21- 8

1 6 8 4 6 1 6 8 5 6 6 4 8 6 1

-----------------------------------------------

L Q M Y N O R X O Q Q O M A K

6.3.8 The increasing complexity of procedures

As time passes, the use of the C-36 becomes increasingly complex to maintain a sufficient level of security. Here is a first example dating from November 1943 (SHD-11P189 1944):

Telegram to be encrypted - Danaide at Base Danaide-Destructeur-

Digitale-Artillerie-divisionaire-Deesse - Text - N ° 141/2 CH.

Following telegram 134/2 CH relating to modification of C.36

encryption.

For reading cipher text subject to paragraph 5 of the aforementioned

telegram. The first and all odd groups will be reversed. The

following example text: PAXMC HZLBS RQVOJ ... will be collected

CMXAP HZLBS JOVQR ... Make an acknowledgment of receipt.

PC on 11/15/43, The Cipher Officer.

If we compare the method using a numerical code to that using substitution

alphabets, we notice that there is no longer any need to distribute Table

B (which contains the alphabets). If, moreover, the configuration of the

pins is transmitted by radio in the form of coded sentences (LE ZOUAVE A

DIT …), there is also no longer any need to distribute Table A. In short,

there is no longer a need to distribute documents to share the keys. This

practice greatly reduces security but greatly facilitates the distribution

of keys.

Note: Well after having formulated this hypothesis (different calage letter for each message), I had confirmation of it by analyzing the numbers present on decipherment tapes coming from two C-36 messages encrypted on June 23, 1943. The letter/number correspondence gives the calage letter "I" for the 1st message and the calage letter "D" for the 2nd message.

For the moment, we can see that the packaging procedures are complex. In fact, unfortunately I have discovered several documents that show that they were even more complex than first thought (SHD-11P189 1944):

From the Commanding General of the 1st Armored Division to the

Army General, December 9, 1943 -

I have the honor to report that, with reference to note

904/CH/CAP of October 21, 1943, the following incidents were

noted during the month of November.

- Mechanical incidents: None.

- Incidents relating to encryption:

Method C-36: For telegrams from units of the Divisions: 2

telegrams received with the 2nd key group not inverted, 1 of

which forgot to set the conventional letter. A telegram with

2 same letters in a pronounceable key ...

- Transmission incidents: For telegrams received by radio,

many errors are noted ...

1st Armored Division - … Mascara - May 17, 1943 - Instructions

for the Bureau du Chiffre - … C-36 cipher machine… Installation

of the interior secret elements by applying Table A provided by

the Commander-in-Chief. Placement of certain pins in active

position. Establishment of a conventional letter. See Chapter

III Deciphering 3rd paragraph of the note from the Commander-in-

Chief ... either the DHERA key, the conventional letter will be

E ...

Danaide à Baptiste - 03/26/44 ... Your telegram 25059

indecipherable but the key is correct. Please check “calage”

letter and “chiffrante” letter.

A new expression appears: "lettre conventionnelle" (conventional letter). Is

this a new concept or a new name for either the “calage” letter or the

“chiffrante” letter? If we interpret it as referring to the “calage” letter,

is it possible to interpret these three texts by imagining that the “calage”

letter (from which the slide derives) would be variable from May 1943 for

each message and would correspond to the middle letter of the first indicator

group that encrypts the message key by means of substitution alphabets (at

the time). If this is really the case, it would greatly improve security but

complicate encryption and packaging. Incidentally, in the first document, we

discover that there is encryption supervision in this period.

In March 1944, a new procedure appeared. The use of the C-36 becomes even more complex: (if it is possible!). The document that describes this method (which is not particularly clear) specifies the location of the key groups, which depend on the group concealing the "chiffrante" letter (SHD-11P189 1944).

TELEGRAM TO BE ENCRYPTED - Danaide to Holders C.36. - Text -

N° 52/2 CH-TS. Addendum relating to encryption by C36.

Addition to Chapter B, Section Z notice 27 CH/CAB, following

instruction: group concealing the "chiffrante" letter is

counted to determine the place of the key groups - STOP -

If total addition of the first 2 digits on the left to the

last 2 digits on the right is ONE, I repeat ONE, the 1st key

group or the second according to the case is placed

immediately after the group concealing the "chiffrante"

letter. The rest without change. PC On March 23, 1944, The

Cipher Officer.

6.3.9 Other procedures

When a machine is not in use, it must be put on the transport key (pins in passive position).

Bureau du Chiffre - Algiers, May 9, 1944 - Subject: Security

of the encryption - Memorandum -

It was brought to the attention of the Colonel Director of

the Bureau du Chiffre that cipher machines C-36 and Converter

had been transferred to the higher unit by formations that had

not taken the care to put the interior elements into the

passive position. There is serious negligence here that could

compromise the encryption security... The Colonel Director of

the Bureau du Chiffre, Signed: Joubert des Ouches.

6.3.10 Example of message (in plain text)

Here is an authentic sample message (SHD-11P187 1944). On the front, the undrafted message and on the back, the raw message (the strip emerging from the C-36 stuck on the slip). The tapes glued (on the back):

NUM WUBE SUR WU REPONSE MESAGE NUM WJU SUR CH

INDIQER POSITION AINSI SUIT SP MA POSITION EST

MOSTAGANEN WN SUR WOCCMMC NUM WON Q O SP

The message (on the front):

TELEGRAM TO ENCRYPTION - DANAIDE to AD

Registration number at number 353 ... Received at number 19h.

Shipped to AD at 8 p.m.

TEXT

N° 298/2 - RESPONSE MESSAGE N ° 42/CH. INDICATE POSITION THUS

FOLLOWS STOP MY POSITION IS MOSTAGANEN 1/200,000 N ° 2I Q O -

STOP

PC November 5, 1943

From the encryption of the numbers, we can deduce the setting of the “calage”

letter. Here it corresponds to the letter "T" (slide = 2), which also

confirms the use of the C-36. In fact, for a time, the French procedures for

encoding the numbers of the M-209 resembled the procedures of the C-36. We

only had strings in the decryption tape beginning with the letter "W" and

ending with a space, for example, WBFK. The cipher clerk also received a

letter/number correspondence table (0 = K, 1 = C, 2 = G, 3 = B, 4 = F…) at

the same time as the keys. It should be remembered that the American method

recommends spelling the digits: 340 was coded "THREE FOUR ZERO" [1]. Ultimately,

the real criterion for differentiating a C-36 tape from an M-209 tape is the

shape of the characters.

Footnote:

[1] As we have seen, the French troops disembarking in Provence abandoned

the French procedures for using the M-209 and used only the American ones

(cf. 6.2).

6.4 German cryptanalysis

6.4.1 German decryption

After the overthrow of France in June 1940, German cryptologists had plenty of time to crack the C-36 and B-211 systems (cf. 5.5). As the B-211 and C-36 cipher machines were not part of the encryption methods of radio communication authorized by the Germans, they could not intercept their traffic, which was only wired. However, as soon as the French troops from North Africa integrated the Allied device, the airwaves filled with messages encrypted in B-211 and C-36. German cryptologists were ready and easily deciphered the C-36 traffic but, to their astonishment, failed to read the B-211 traffic [1] (TICOM I-58 1945):

TICOM I-58 - Interrogation of Dr. Otto Buggisch of OKW/Chi.

Roughly end of 42 or beginning of 43 Reappearance of C-36 messages

in De Gaulle traffic. Decoding by means of the method developed

earlier by Dr. Denffer; likewise B-211 messages appear, which

however do not decode according to the theoretically worked out

method.

Decryption is facilitated by the fact that the internal key remains in function for a long time (several weeks or even several months; cf. 6.3.4) and the use of stereotyped beginnings (cf. 6.3.2).

TICOM IF-107… Before describing his work on the Converter M-209, "G"

advised us that a French Hagelin machine had been originally broken in

1940. He called this machine C-36, and advises that it had fixed lugs

(which he called cams) and that the kicks were always 1, 2, 4, 8 and

10 [2]. He stated, however, that the internal settings (which he called

constellations) were changed only every few months. Solution was

effected through the fact that nearly all messages started with

"Refer" [3]. The original solution was accomplished from the beginnings

of about 50 messages. He also advises that when the internal settings

were changed the new traffic was sent to Berlin by courier and that

Berlin was usually able to effect the solution within 48 hours.

From the beginning of 1944, the various changes in procedures complicated

the work of the Germans, in particular, the new indicator system

(cf. 6.3.7). The full traffic reading was only able to

be performed after breaking this system. But internal keys continued to be

broken, mostly by cribs as well as by a statistical method that required obtaining

messages of at least 400 characters. After the French emit the keys over

the air, the work of the Germans is obviously made easier (TICOM I-92 1945).

TICOM I-92 - Final interrogation of Wachtmeister Oto Buggisch.

Complications in C36. Buggisch could recall no "complicated

enciphering device," unless he had meant to refer to the new

indicator method introduced in January of 1944. The old indicator

system, changed in its details in 1942, had been a letter

substitution table, which had been simple. The new system was

based on numbers, but he could give no details. Relative internal

settings continued to be recovered and a high percent of the

traffic solved on cribs and statistics (for any message over 400

letters) until the indicator was broken in the late summer of 1944.

About the same time in 1944, the French had adopted a system of

sending internal settings by means of an ordinary sentence for

each wheel, of which the first so many non repeating letters

gave the active lug positions [4]. This system was first reported

in a broken code message; the knowledge that it existed was of

academic interest only, as no keys were gained from other systems.

Buggisch spoke specifically of the successful solution of the C-36 in 1943

on de GAULLE traffic to CORSICA. He also said that the date and strength

of force of the landings in Southern France were largely given away by

broken C-36 traffic.

The statistical method was not described by Buggisch. However, I think this is the reconstruction of the pins of Wheels 17 and 19 using the general method approach (cf. 5.5). Then, it is easy to place cribs that match the inferred configurations and gradually reconstruct the pin configurations of the other wheels.

Notes:

- A good indicating system is an extremely important part of the security of a cryptographic system. Indeed, if the enemy has succeeded in breaking the key of the day, they still need to find the message key for each message. If the indicator method is weak and the enemy has reconstructed it, they can decipher all the messages as if they were the real recipients. This was the case for the C-36 with the use of substitution alphabets, which allowed the Germans to read all the messages of a period as soon as the internal key was broken. In contrast, the digital indicator method offered better security. As long as it was not broken (which happened late), the Germans had to find the key to each message individually. Using probable words helps to achieve this, but also slows down the deciphering work considerably.

- If my assumption is correct about the operation of the digital indicator used from January 1944, the slide is modified for each message (cf. 6.3.7). The work of German cryptanalysts is obviously becoming more complex. But they can still break every post with the stereotypical beginnings. Knowing the values of the Pins obviously simplifies the verification of the hypotheses.

TICOM I-58

Winter 43/44 ... C36 messages with complicated enciphering technique,

solved in spring (Le zouave du pont d’Alma m’a dit).

Footnotes:

- [1] The French added four rotors to the B-211. The traffic of this machine will remain unbreakable until the end of the war.

- [2] The position of Lugs 1, 2, 4, 8 and 10 is a priori incorrect. It is difficult to imagine where this mistake originated.

- [3] As noted earlier, analysis of the printed tapes from the C-36 shows the beginning "NOKW" or “NUMK” is much more frequent than "REFER".

- [4] It is necessary to understand "active pin positions."

6.4.2 Finding the external key of a message using a probable word

As reported, until the digital indicator system was known, the Germans had to individually break each message. The German cryptanalyst Alfred Pokorn describes the method for a message encrypted in M-209 (TICOM-IF-175 1945, paragraph “Breaking a Third Message”). In the next paragraph, I have adapted his method to a C-36 encrypted message.

Suppose we know the internal key. We have a message ciphered with this key. How to find the external key? If we suppose that the message begins with a probable word (a crib), we can deduce the first pins for each wheel and there we can deduce the external key.

Note: The methods which make it possible to find the internal key (messages in-depth, stereotyped start) only make it possible to discover a relative internal key. The true internal key does not need to be known to decrypt messages. When we decrypt other messages, we will only know message keys relative to the first key we acquired and which we set arbitrarily to AAAAA.

Example:

Ciphered message: EBGLF AMNDU PWIU ...

Plain message (supposed): REFER K ...

Internal Key:

- Position of key wheels pins:

Wheel 1 (25): A__DE_G__JKL__O__RS_U_X__

Wheel 2 (23): AB____GH_J_LMN___RSTU_X

Wheel 3 (21): __C_EF_HI___MN_P__STU

Wheel 4 (19): _B_DEF_HI___LN_P__S

Wheel 5 (17): AB_D___H__K__NO_Q

- Slide: 0 (letter A)

The method: We can guess the pin settings that explain the K key values

from the values of the ciphered text and the corresponding crib

(cf. 2.1):

C[i] = (S + K[i]) - P[i]

C[i] = Ciphered letter number i, S = Slide, K[i] = Key number i,

P[i] = Plain letter number i

In the example, S = 0, then: K[i] = C[i] + P[i]

C P K Pins[1] Pins[2] Pins[3] Pins[4] Pins[5] Overlaps: 1-5,2-5

1 lug 2 lugs 3 lugs 7 lugs 14 lugs

----------------------------------------------------------------

E R 21 ? 0 0 1 1 = 14+7

B E 5 0 1 1 0 0 = 3+2

G F 11 1 0 1 1 0 = 7+3+1

L E 15 ? 1 0 0 1 = 14+2-1 (overlap)

F R 22 ? 1 0 1 1 = 14+7+2-1(overlap)

A K 10 0/1 0/1 1/0 1 0 = 7+3 or 7+2+1

For the second wheel, the pattern 010110 is impossible, then the active pins

for the sixth letters are 11010. We know the pattern for the first wheel:

?01??1 (ou .01..1). Apart from the first wheel, we can deduce the pseudo

external key: [BFMPV]IGSK. We can try each character B, F, M, P, and V and

decipher the following letters (MNDU...) of the cryptogram.

A__DE_G__JKL__O__RS_U_X__

.01..1 (key: B)

.01..1 (key: F)

.01..1 (key: M)

.01..1 (key: P)

.01..1 (key: V)

The message key found is PIGSK. The genuine external key is then GAULE (do

not forget there is a shift between the active pins and the letters that

are visible on the benchmark).

References

- Muller, A, 1983. Le Décryptement, Presses Universitaires de France.

- SHD – 10 P 237. 1943. Télégrammes Départ – Arrivé. “PC-JOSEPH”. Période du 22 Novembre 1943 au 4 Février 1943.

- SHD – 10 P 237. 1943. Télégrammes Départ – Arrivé. “PC-JOSEPH”. Période du 22 Novembre 1943 au 4 Février 1943.

- SHD - 10 P 238. 1943. Détachement d'armée française PC Jean - 1942 (20dec)-1943

- SHD - 11 P 187. 1944. 1er Division Blindée – Section du chiffre – E.M: 2e Bureau – Télégrammes expédiés 9-6-43 au 21-12-1944. 1943-1944.

- SHD - 11 P 189. 1944. 1er Division Blindée – Section du chiffre – E.M: 2e Bureau – Courrier expédié et reçu concernant la sécurité du chiffre – 16-11-43 au 9-11-44. 1943-1944.

- SHD - B10 1460. 1944. EMGG EMA 412 R 15 Teleg. depart avr-juillet 1944 EMDN service du chiffre.

Web Links

- TICOM I-58 – Interrogation of Dr Otto Buggish of OKW/Chi – Aug 1945 (link).

- TICOM I-92 – Final interrogation of Watchtmeister Otto Buggisch – Sept 1945 (link).

- TICOM IF-107 – Interview of Werner K.H. Graupe, PW, nov 1944 (link).

- TICOM IF-175 – Report by Alfred Pokorn, of OKH/CHI, on M.209, 14th December, 1945 link).